Two Edible and Drought-Tolerant Sumacs for Food, Medicine, and… Male Pregnancy.

BELOW: Rhus trilobata (lemonberry sumac)

Image 2: Rhus trilobata (lemonberry sumac). This bush was found on the campus of Colorado State University-Pueblo. Photograph taken on 26 September 2017.

AKA: skunkbush, basketweed, selet (Cahuilla).

BELOW: Rhus typhina (staghorn sumac)

Binomial Etymology — Rhus means sumac (Borror, 1960). The specific name, typhina, relates to the seed-heads having the texture of antlers covered in velvet (Linné, 1970).

tri- means three; -lobata refers to the lobes observed on this species’ leaves (Borror, 1960).

Binomial Pronunciation —ROOSE try-LOBE-ah-tah

ROOSE tie-FEEN-ah

USDA Status —Both Rhus species dealt with in this article are native.

Family — Anacardiaceae (Cashew Family)

Family Characteristics — Leaves are three-lobed or pinnate with single-seeded (often hairy) berries of a red or white color (Epel, 2004).

Family Members — Mango, cashew, & pistachio (Epel, 2004).

Introduction

Let’s play the ‘I Say You Say’ game.

Okay. Ready?

When I say SUMAC, you say…

POISON!

I had a feeling you might say that. Likewise, if your name is J. W. Gacy, it does NOT matter how nice you are… people are going to think of a psychotic clown when you introduce yourself. The same thing happens to our edible sumacs. The word “sumac” often conjures images of boils and unrelenting misery.

And, yes, eating poison sumac will likely kill you in an unimaginably horrific way.

HOWEVER…

Poison sumac — like serial-killing clowns — are relatively rare compared to the friendlies, and thankfully, it is downright difficult to mistake poison sumac for the edible species discussed in this post. I’ll give you one great distinguishing characteristic (among many): poison sumac have white berries and these edible sumacs have red berries.

Image 3: Poison sumac. Notice the white berries.

Poison sumac… white berries… John Wayne Gacy…white face paint. Feeling better? Great! Lets take a walk.

Edible sumacs can make a fantastic lemon-flavored drink, tan leather of refined quality, create a spice mixture to elevate your barbecue, protect your hands from blistering when grabbing cooked dog meat, and, legend has it, these sumacs may even help men — ahem — to conceive and deliver babies. As you will see, I made none of that up; these Rhus species may just make some of your more embarrasing dreams come true. Buckle up, weirdos; we are going for a ride!

Habitat

Rhus trilobata will grow in a range of habitats including poor, dry, and slightly alkaline soil sites.

Image Retrieved from https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/rhutri/all.html

Similarly, Rhus trilobata thrives in drier soil conditions, on the margins of forests, gravely/rocky sites, and on the sides of roads.

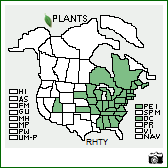

Rhus typhina range: Image retrieved from https://plants.usda.gov/maps/thumbs2/RHTY.png

Description

Rhus typhina (staghorn sumac)

The leaves are pinnately compound, and alternate containing a number of lanceolate leaflets that have serrated leaf margins. These compound leaves can be 1–2ft long and contain ten to thirty individual leaflets. Thirteen leaflets are visible in the compound leaf below (Image 4).

Image 4: A staghorn sumac compound leaf (photographed 20 September 2017).

The berries are actually classified as drupes. The red drupes are often covered in sticky hairs (see Image 5 below), occurring in remarkable flame-like clusters (see Image 9 below). These clusters sometimes hang on throughout the winter, but will appear at their brightest in mid-summer.

Image 5: A sticky staghorn sumac fruit cluster (photographed 20 September 2017)

The twigs will be downright furry. The growth habit of R. typhina is that of a dwarf tree, only reaching a maximum(ish) height of 25ft (8 meters) or so.

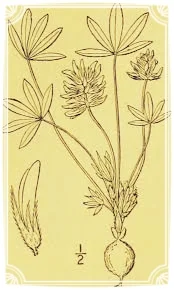

Rhus trilobata (lemonberry sumac)

As seen in Image 6 below, the leaves of lemonberry sumac are oak-like, smoothly serrate at the margins (pinnately lobed), and occur in threes in an alternate pattern (see Image 7 below). In the springtime, before the leaves emerge, numerous 5-petaled yellowish flowers will awake from the catkins pictured in Image 6.

Image 6: Lemonberry sumac leaves (photographed 26 September 2017 at Colorado State University-Pueblo)

Image 7: Lemonberry sumac. This picture shows the alternate arraignment of the leaves (photographed 26 September 2017 at Colorado State University-Pueblo)

The crinkly berries are not perfectly round, are born in clusters, and have sparsely fine hairs on their sticky surface as seen in Image 8 below.

Image 8: A close-up of lemonberry sumac drupes (photographed at Colorado State University-Pueblo 26 September 2017).

The bush can grow from two to about thirteen feet tall on the maximum end. Thirteen feet is pushing it.

Edible Uses

In the absence of a recent rain, Rhus berries slowly exude a coating of malic acid onto their surface (Laboratory Guide To Archaeological Plant Remains From Eastern North America, n.d.). This same acid is dominantly responsible for the sour flavor in apples and contributes to the sour flavor in lemons and other citrus fruits as well (Sortwell & Woo, 1996). So, when soaked in water and sweetened, the acidic coat on Rhus fruits dissolve to make a delicious ruby-colored drink that tastes much like a fruity lemonade called “rhus juice.” My lovely wife, Sophia, and I have tried this with R. typhina (staghorn sumac) and it was wonderful. However, do not boil the seed-head as this may infuse an astringent dose of tannins into your drink and those will bully away any pleasant flavors. Steep your cheese-cloth wrapped seed-heads in coolwater until you achieve a pale-to-ruby-red color, sweeten, add ice, and try not to like it.

For the best results, harvest the fruit clusters in the late summer/early fall after a bit of a dry spell.

A related sumac that does not occur in the Americas, Rhus coriaria, is widely used as a spice in Middle Eastern cooking and our native Rhus cousins can be used in much the same way (Kossah, 2009). A much acclaimed spice mix, Za’atar, is made with this sumac and is said to give a unique lemony quality to meats and other foods.

A super-concentrated rhus-juice can be made into a reportedly delicious jelly with added pectin (Thayer, 2003), and Jack Keller — who legendarily had a country wine recipe for just about anything that lives on Earth— had his own recipe specifically for staghorn sumac wine (Keller, 2000).

Recipes for the above uses can be found in the Recipe Challenge section below.

Image 9: staghorn sumac (photographed 26 September 2017 at Colorado State University- Pueblo)

Folk Remedies

The fruits were steeped as a tea to treat diarrhea; the root of the R. typhinawas used in concert with purple coneflower (Brauneria purpura) in order to treat the symptoms of unspecified venereal diseases (Tantaquidgeon, 1942).

Samuel Thomson, a controversial “medical” herbalist in the 19th century, lauded the use of R. typhina and R. trilobata to make a sore throat, sore mouth, and germ killing mouthwash and an ulcer, recurring fever, tuberculosis, syphilis-fighting poultice (Riddell, 1919). Further, Thomson lauded sumac tea as a leukorrhea (an ailment presenting with a thick white vaginal discharge) curative (Comfort, 1867).

The Hočąk peoples utilized both the inner bark and root bark of R. typhina to pound into a poultice to treat sores (Kindscher & Hurlburt, 1998).

Sumac berries were macerated to treat flatulence, to stimulate the senses, and to alleviate troubles with muscle spasms (Henkle, 1913).

R. trilobata was used by the Blackfoot, Yokia, Round Valley Indians, Paiute, and Montana peoples for the topical treatment of smallpox sores (Moerman, 2009). The Hopi used R. trilobata root as a deodorant (Moerman, 2009).

Pharmacological Effects

A tannin (with a ridiculously long chemical name) extracted from R. typhinahas been shown to bind aggressively with alpha-synuclein (a hallmark protein associated with the development of Parkinson’s disease); this activity bodes well for the use of this plant extract as a preventative drug against Parkinson’s disease (Sekowski et. al., 2017).

Magic

R. trilobata was used to coat and protect the hands whilst plunging them into boiling water to retrieve your cooking dog meat (Moerman, 2009). I will tell our dog of this use the next time he pee-pees in the house.

History

The hulking majority of references to American native sumacs refer to the gathering of sumac leaves and stalks to create a tannin-rich extract used for the tanning of leather. The quality of sumac tannin was a hot topic among nerds of the 19th and early 20th century… especially when related to hat-making and leather book-binding. Leather was perceived to have an almost everlasting durability when tanned with sumac (American Sumac, 1920). This practice was of such apparent importance, a researcher is left wading in a veritable sea of archaic tanning manuals looking for anything else.

Literature

An ancient drama written by the Ynca peoples of Peru called Ollanta was translated in the 19th century and featured a character named Yma Sumac (Markham, 1871). After reading the short drama, it is still unclear what the significance of her name is, and how it is connected to Rhus spp.

Nutrition

R. typhina seeds and fruits, in past studies, have shown to carry impressive amounts of dietery oil (6.5%) and nutritional phytochemicals (30.8%) (Carr et al., 1986). The berries also contain high levels of calcium and potassium malites (Epel, 2004) as well as many antioxidants including four rare anthocyanins (Lai et. al., 2014).

Other Uses

The leaves of R. typhina were harvested industrially in the early 20th century to use in dye making (Utilization Abstracts, 1947). The split stems of R. typhina where important in the construction of Cahuilla baskets (Pearlstein et.al, 2008).

Recipes Challenges

Seven awesome-sounding sumac spiced recipes

Weird Facts

In addition to being used to protect your delicate hands from getting burned on dog meat, the Cheyenne maintained that an old man was once able to get pregnant and give birth to a child after using R. trilobata as a medicine (Moerman, 2009). Either the Cheyenne where having fun with some dreadfully credulous ethnobotanist or an old man pooped out an infant in front of some very impressed Cheyenne people one day. To me, it doesn’t matter which scenario played out; either way… I like it.

By: K.D. Healey

Reference

Tantaquidgeon, G. (1942). A study of Delaware Indian medicine practice and folk beliefs. Harrisburg, PA: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Dept. of Public Instruction, Pennsylvania Historical Commission.

Riddell, W. Renwick. (1919). The pharmacopoeia of another botanical physician.

Carr, M. E., Roth, W. B., & Bagby, M. O. (1986). Potential resource materials from Ohio plants. Economic Botany, 40(4), 434–441. doi:10.1007/bf02859655

Kindscher, K., & Hurlburt, D. P. (1998). Huron Smiths ethnobotany of the Hocąk (Winnebago). Economic Botany, 52(4), 352–372. doi:10.1007/bf02862065

Utilization Abstracts. (1947). Economic Botany, 1(3), 275–352. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4251858

American sumac: a valuable tanning material and dyestuff. By F. P. Veitch … J. S. Rogers and R. W. Frey … Issued July 26, 1918; rev. Nov. 6, 1920.

Henkel, A. (1913). American medicinal flowers, fruits, and seeds. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.

Borror, D. J. (1960). Dictionary of Word Roots and Combining Forms (1st ed.). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Linné, C. V., Juslenius, A. D., Torner, E., & Höjer., L. M. (1970, January 01). Centuria I.-[II.] plantarum /. Retrieved September 25, 2017, from http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/36017979#page/18/mode/1up

Elpel, T. J. (2004). Botany in a day: Thomas J. Elpels herbal field guide to plant families. Pony, MT: HOPS Press.

Comfort, J. W. (1867). The practice of medicine on Thomsonian principles: adapted as well to the use of families as to that of the practitioner : containing a biographical sketch of Dr. Thomson … with practical directions for administering the Thomsonian medicines … and a materia medica, adapted to the work. 7th edition. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston.

Laboratory Guide To Archaeological Plant Remains From Eastern North America. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2017, from https://pages.wustl.edu/fritz/rhus-spp

Sortwell, D., & Woo, A. (1996, March 28). Improving the Flavor of Fruit Products with Acidulants. Retrieved September 25, 2017, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.548.4424&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Kossah, R., Nsabimana, C., Zhao, J., Chen, H., Tian, F., Zhang, H., & Chen, W. (2009). Comparative Study on the Chemical Composition of Syrian Sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) and Chinese Sumac (Rhus typhina L.) Fruits. Retrieved September 25, 2017, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.575.2483&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Moerman, D. E. (2009). Native American medicinal plants: an ethnobotanical dictionary. Portland, Or.: Timber Press.

Pearlstein, E., Brer, C. D., Gleeson, M., Lewis, A., Pickman, S., & Werden, L. (2008). An Examination of Plant Elements Used For Cahuilla Baskets from Southern California. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 47(3), 183–200. doi:10.1179/019713608804539600

Thayer, S. (2003). Sumac The Wild Lemonade Berry. Countryside and Small Stock Journal,87(4), 49–51.

Sekowski, S., Ionov, M., Abdulladjanova, N., Makhmudov, R., Mavlyanov, S., Milowska, K., . . . Zamaraeva, M. (2017). Interaction of α-synuclein with Rhus typhina tannin — Implication for Parkinson’s disease. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 155, 159–165. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.04.007

Lai, J., Wang, H., Wang, D., Fang, F., Wang, F., & Wu, T. (2014). Ultrasonic Extraction of Antioxidants from Chinese Sumac (Rhus typhina L.) Fruit Using Response Surface Methodology and Their Characterization. Molecules, 19(7), 9019–9032. doi:10.3390/molecules19079019

Markham, C. R. (Clements Robert). (1871). Ollanta: an ancient Ynca drama.London: Trübner & Co.